Remembrance

Disclaimer: This article includes some chronological history of the Glenn Miller Army Air Forces Orchestra, which I copied and loosely edited from Wikipedia and the Glenn Miller archives. I wasn’t going to write it any better…

Everyone from my generation working in film music has one primary inspiration in common—Star Wars. When I moved to Los Angeles, the pure love for John Williams’ scores, starting with this one, was universal amongst my peers. Whether it was the story, the toys, the filmmaking, or the music, this film seems to be a cultural cornerstone in the lives of all GenXers. I remember seeing it in the theater and liking it, but I didn’t see it multiple times, get any of the toys, or become obsessed with the soundtrack as many others did. When I worked as a music copyist on film and television scores, I studied composing to picture. I developed a heightened appreciation and understanding of the narrative impact of orchestration and leitmotifs on storytelling. On days when I wasn’t working, I often went to see movies (repeatedly), analyzing the craft of making and scoring them. For the first (and only) time in my life, I was current on all the films in theaters. One of those films, Saving Private Ryan, also had a tremendous emotional impact on me—as it did for many people. I saw a late-morning showing in a small theater in San Luis Obispo. Other than me and a few accompanying family members, there were twelve to fifteen old men—veterans adorned in all their insignia. The extended opening scene depicting the landing on Omaha Beach is a profoundly moving piece of dramatic filmmaking (with very little music). The film tapped a well of empathy and understanding in me.

The story of “the greatest generation” is often framed by sacrifice. This flows poignantly from the fate of over four hundred thousand American soldiers who lost their lives during World War II. Still, it extends to all who served and stories of family hardship marked by absence, rationing, and intense labor back home. It also colors ideals of “selfless service” associated with this generation in the post-war years. This perspective—sacrifice—leads to gratitude, which is celebrated and deserved. But its co-existent reality—the shadow—is the unimaginable, severe trauma inflicted upon many of the nearly ten million young (American) men drafted into World War II—whose fortune was snared by a letter from the Department of Defense lying in wait. The collective reverberations of these personal traumas immeasurably impacted our social fabric, politics, and economy throughout the remainder of the twentieth century with a cold-war worldview at home and abroad marked by anger, fear, and suspicion—still shaping the world I grew up in, in the 1970s and 1980s. To bear witness to a powerful depiction of what caused that trauma—making the unimaginable vividly imaginable—in the presence of men who still carried its weight inside them in their elder years left me with a visceral understanding of their life-long suffering. “Trauma is not what happens to you but what happens inside you.” What many sacrificed for their country included their peace of mind.

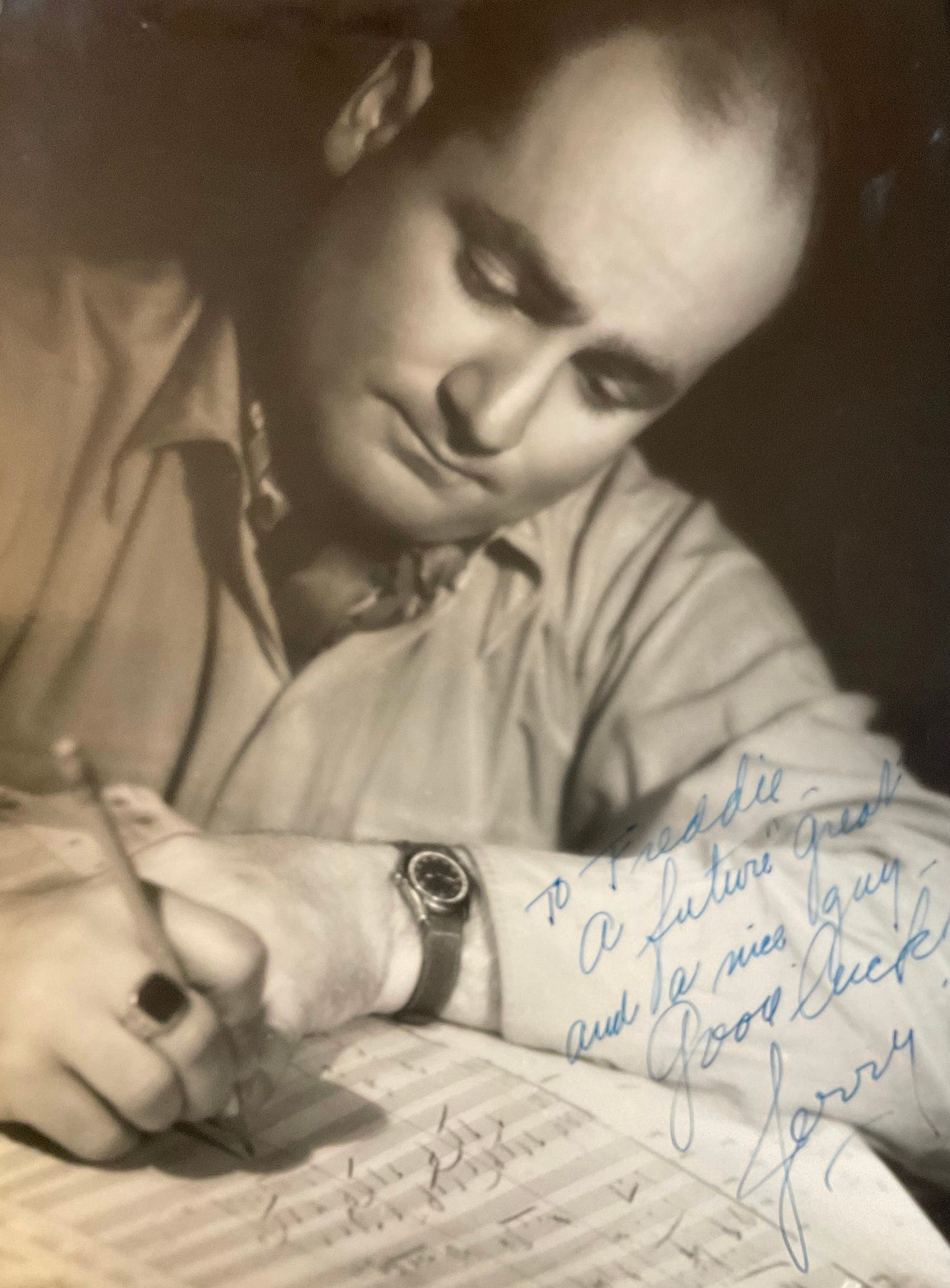

I recently did an extensive cleaning and some mechanical work on a Selmer Balanced Action alto saxophone for Chris Guerra, who has brought me several horns to work on in the past year. This Selmer had been his dad’s. Chris’ father, Freddy Guerra, was the youngest member of Glenn Miller’s Army Air Forces Orchestra. His fate twisted twice in 1943 at the age of twenty. While he stood in a line of recruits boarding a train in Penn Station destined for boot camp down south before being shipped to combat in Europe, an officer tapped him on the shoulder and said ‘come with me, you’ve got different orders’. His friend from Boston, Generoso Graziano, known professionally as Jerry Gray, sent for him to audition on the Yale University campus.

In 1936, Jerry Gray joined Artie Shaw’s "New Music" orchestra as the lead violinist and became a staff arranger a year later. He arranged some of the band's most popular tunes, including "Carioca", "Softly, As in a Morning Sunrise", "Any Old Time", and "Begin the Beguine." In November 1939, when Artie (famously mercurial) broke up the band and moved to Mexico, Glenn Miller called Gray and offered him a job arranging for the Glenn Miller Orchestra—the best-selling recording band from 1939 to 1942. After Miller broke up his civilian band in September 1942 to enter the Army Air Forces, he used his connections to have Gray posted as the chief arranger for the "Band of the Training Command," later known as the Glenn Miller Army Air Forces Orchestra. Years later, Jerry confessed to author George T. Simon in his book The Big Bands, "To me, Glenn's band didn't swing like Artie's. ... But after I made up my mind to accept things as they were, things started to click. ... He was a businessman who appreciated music. ... I may have been happier musically with Artie, but I was happier personally with Glenn."

After being turned down by the Navy, Glenn Miller applied for a commission in the Army, with whom he had privately explored the possibility of enlisting. During a March 1942 visit to Washington, Miller met with officials of the Army Bureau of Public Relations and Army Air Forces. On August 12, 1942, he sent a three-page letter to General Charles Young of the Army Service Forces, outlining his interest in "streamlining modern military music" and expressing his "sincere desire to do a real job for the Army that is not actuated by any personal draft problem." Miller directed the Second AAF Radio Production Unit and Orchestra, broadcasting and recording from New York. His unit was authorized on March 20, 1943, and billeted at the AAF Training School at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Freddy’s bandmates were a talented mix of jazz musicians from major big bands and musicians from leading symphony orchestras.

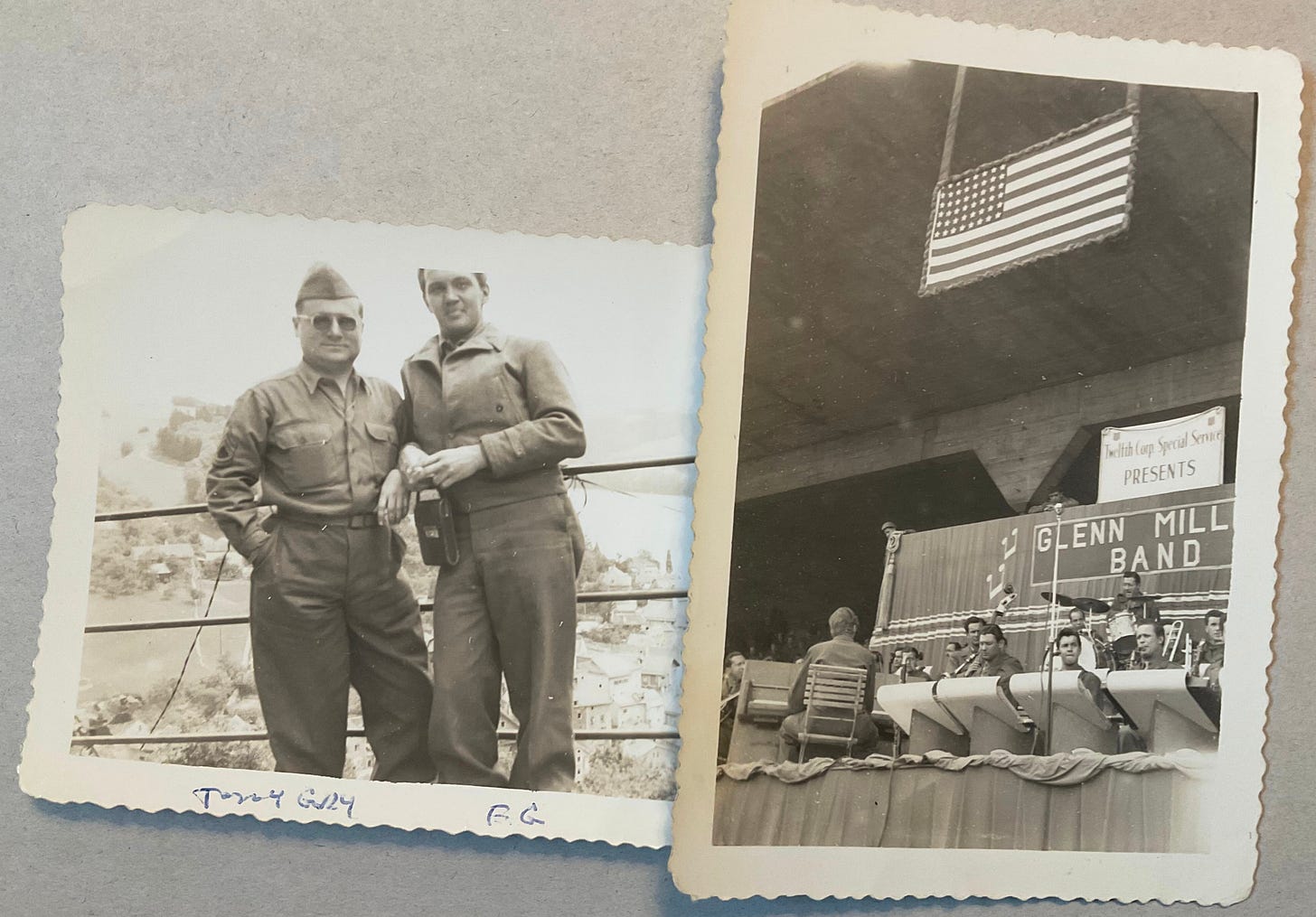

After auditioning with Glenn for a week, Freddy joined the band with Henry Mancini, popular civilian bandleader and drummer Ray McKinley, Vito Pascucci playing in the trumpet section and acting as the band’s repair technician, Zeke Zarchy on trumpet, and singer Johnny Desmond. From New York, Freddy and the band broadcast I Sustain the Wings. This weekly series was first carried by CBS starting on June 5, 1943, and then by NBC from September 18, 1943, through June 10, 1944, when they deployed overseas. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower sent a cable to Washington requesting the transfer of the Miller AAF unit for radio broadcasting and morale. With the impending D-Day invasion of northwest Europe, the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) was establishing a combined allied radio broadcasting service. Eisenhower cited the Miller organization as the "only organization capable of performing the mission required." Miller and radio producer Sgt. Paul Dudley flew to London on June 19, and the band followed aboard the RMS Queen Elizabeth, which served as a troopship.

On July 9, 1944, Miller's 51-piece orchestra and production personnel started broadcasting musical programs over the AEFP under BBC technical supervision. The programs included: "The American Band of the AEF" (full orchestra), "Swing Shift" (T/Sgt. Ray McKinley dance orchestra), "Uptown Hall" (Sgt. Mel Powell jazz quartet), "Strings with Wings" (Sgt. George Ockner, concertmaster and the string section), "Song by Sgt. Johnny Desmond" (vocalist with orchestra directed by M/Sgt. Norman Leyden) and "Piano Parade" (piano solos by Pvt. Jack Rusin and Sgt. Mel Powell). The orchestra also appeared for the Office of War Information's Voice of America European outlet. The American Broadcasting Station in Europe (ABSIE) broadcast daily to occupied Europe and Germany. The band kept an extensive schedule of personal appearances in England at primarily American air bases. Visiting American celebrities Bing Crosby and Dinah Shore appeared on their radio programs. Shore joined Miller for a recording session at Abbey Road Studios, where the orchestra recorded their ABSIE German language programs.

"Captain Miller, next to a letter from home, your band is the greatest morale booster in the European Theater." - General James H. Doolittle, Commanding General of the Eighth Air Force.

On December 15th, 1944, the day before the Battle of the Bulge began, Captain Glenn Miller’s plane disappeared over the English Channel while on his way from London-Bovingdon to Paris-Orly ahead of his unit’s relocation from England to France. Despite this tragedy, The Major Glenn Miller Army Air Forces Orchestra appeared as scheduled on December 25, 1944, conducted by Jerry Gray. The unit continued to broadcast and appear throughout Europe through V-E Day until August 1945. It received a Unit Citation from Gen. Eisenhower. The band resumed the I Sustain The Wings series after returning from the European Theater in August 1945. They also recorded V-Discs at RCA Victor studios and recorded broadcasts for the Office of War Information and Armed Forces Radio Service, including “Music from America” and “Uncle Sam Presents." On November 13, 1945, the AAF Band appeared at the National Press Club for its final concert, which President Harry Truman and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King attended. When the band appeared to the strains of Miller's theme "Moonlight Serenade", the president stood and led the audience in a spontaneous round of applause. General Eisenhower and General Arnold congratulated The band for a job "well done.” Their last performance was the I Sustain the Wings broadcast at Bolling Field, Washington, D.C., on NBC radio on November 17, 1945. Its personnel were gradually discharged, and the unit was disestablished in January 1946.

After touring with the band in Europe and throughout the United States after the war, Freddy settled back home in Boston, where he enjoyed a career playing and teaching and raised a family until retiring to Arizona. From 1952 to 1959, he led the Freddy Guerra Orchestra, an 18-piece band at the Totem Pole at Norumbega Park in Newton. It was the premiere ballroom in Massachusetts and one of the largest in the United States. He taught at the New England Conservatory and Berklee College of Music and arranged jingles at the Ace Recording Studio in Boston. He enjoyed friendships with his bandmates until the end of his life. In the 1960s, Mancini recruited him to join his band in Los Angeles (he didn’t), and in his later years, slowed by Parkinson’s, Vito gave him an adaptive Leblanc clarinet that didn’t require shaky fingers to cover the tone holes. Freddy Guerra died on May 17th, 2003, in Mesa, Arizona. He enjoyed a front-and-center seat to a unique and influential piece of American music history. I can’t thank his son, Chris, enough for sharing this story and his family’s photos and trusting me with Freddy’s horn.

From the Air Force Museum:

“In September 1942, Glenn Miller, one of America's greatest dance band leaders of the period, disbanded his orchestra so he could join the Army Air Forces to do his part for the war effort. Within a year, he organized and perfected what has been widely accepted as the greatest aggregation of dance musicians ever forged into a single unit, the Maj. Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band.

The band was transferred from the United States to England in June 1944 and immediately began playing in theaters, clubs, hospitals, hangars and even out in the open -- anywhere that U.S. servicemen could gather. In the 15 months the unit served in Europe, it made more than 350 personal appearances, attended by 1,250,000 military personnel. In addition, it made more than 500 radio broadcasts for the pleasure of millions of other soldiers. It brought "a little bit of home" to the lonely serviceman in foreign lands and was enjoyed by our Allies as well.”