The "Leblanc System" Saxophone

At the end of August, I got a call from someone with three saxophones needing work. She wanted one of the altos brought into play condition for her son to use in the school band and the same with the other alto and tenor, but there was no rush on those. She had someone else drop them off, so the details were conveyed through sticky notes rather than conversation. The alto case with the horn she needed first held a non-descript Conn with most of the lacquer gone. It was dirty and not working, but it didn’t have any dents and looked like it had been well cared for and played often. It didn’t have any engraving, so I was surprised to discover it was from the early 1930s after looking at the serial number. Conns from that period usually have elaborate engravings on the bells. The Conn New Wonder II model from the late 1920s preceded the Conn 6M (alto), 10M (tenor), and 12M (baritone) models of the 1930s, which many people consider the best saxophones Conn ever made. Between those two models are roughly four to five years of “transitional” saxophones evolving towards the M series Artist models. After closer inspection and matching it to pictures on saxpics.com, I sorted out that it was built just a few months before the release of the 6M model but had all of the design characteristics of one—rolled tone holes, bell keys on the LH side of the horn, etc. It needed some work, but it cleaned up and played great.

The 6M design was finalized toward the end of the Transitional period. It marked the beginning of Conn's most famous series of horns: the M series, or "Naked Lady" model, as they are commonly known because of the engraving of a nude female portrait in a pentagon on the bell. So this was an unmarked 6M—an unusual and fun horn to have in the shop—and it played beautifully!

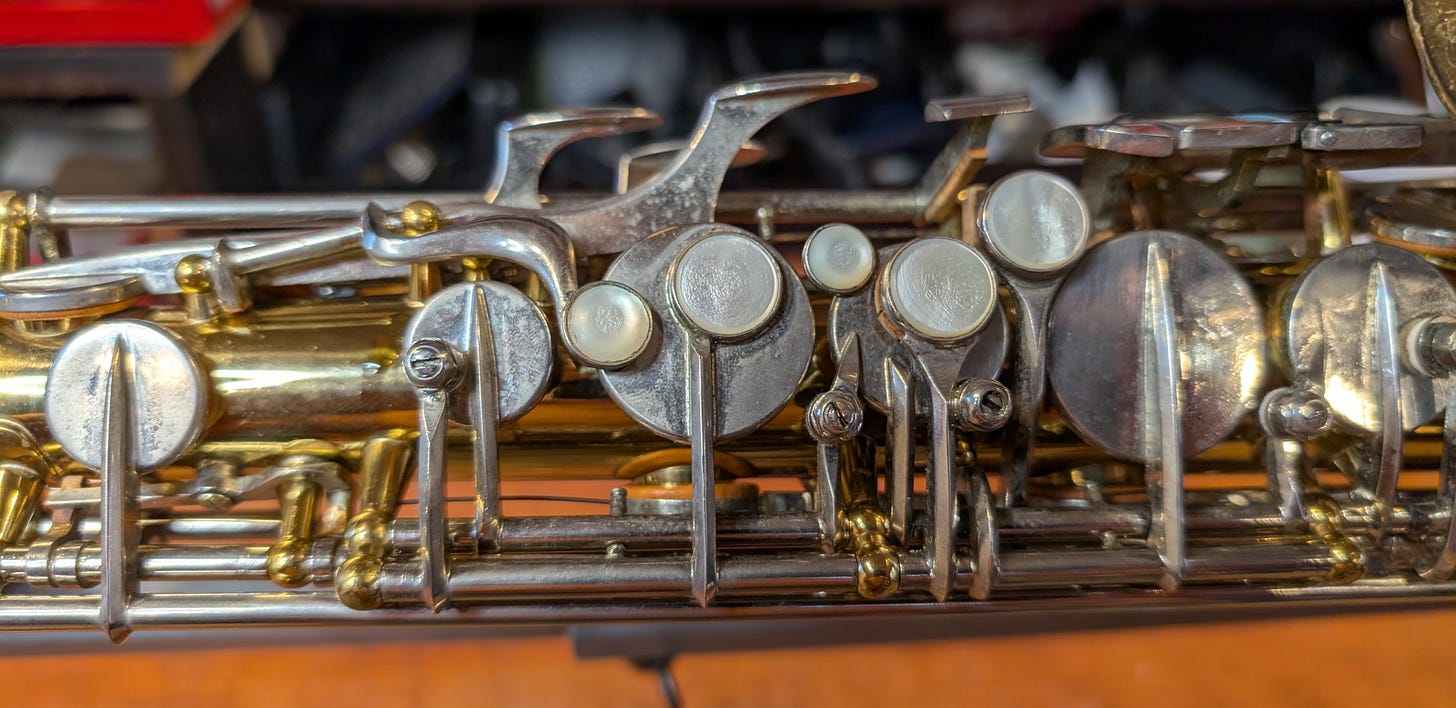

A couple of weeks later, when I finally opened the other alto and tenor cases, I was in for another history lesson. They were both G. Leblanc Paris System 100 saxophones made in the early 1960s. These are rare horns that I have heard about but never seen or played. The Paris System 100 saxophones, following the Rationnel and Semi-Rationnel models, introduced a unique coupling mechanism that allows for additional chromatic fingering options—enabling the player to lower the pitch in the left-hand key bank one semitone by depressing the first, second, or third finger of the right hand. In the same way, you can go between “B” and “Bb” by depressing the “F” key in your right hand, so you can on this horn, “C#” to “C,” “B” and “Bb, and “A” to “G#” using any of the three primary right-hand keys. They also redesigned the venting, eliminating traditionally stuffy notes and creating a more even sound and intonation throughout the range of the instrument.

The Model 100 and 120 "System" saxophones were the latest iteration of instruments designed by G. Leblanc in the early 1930s to alleviate acoustic problems inherent in the standard key system and offer more fingering choices. Few were made — less than two thousand altos and two thousand tenors. The serial number on the alto I had in the shop was in the 1200s, and the tenor in the 600s. I called the woman who gave me the horns to repair, wanting to hear where she got these three collector’s saxophones. She laughed and told me they were her father’s. He was a professional player and proudly played them up until the month he passed away over twenty years ago. They hadn’t been played since.

“One hundred years after the invention of the saxophone, Messrs. Leon LeBlanc; Georges Leblanc; and Charles Houvenaghel developed a unique instrument which offered viable solutions to problems which had plagued saxophonists since the very beginning. By using innovative key mechanisms and following the true Boehm theory of tone hole placement, they produced an instrument which is unsurpassed in technical facility and even voicing. Unfortunately, this complex instrument did not gain wide market acceptance, and was withdrawn after a limited production run. These instruments are very rare, and it is my hope that the new owner of the Leblanc Corporation will give consideration to the re-introduction of this system. I am very proud to have to examples of the “Rationale” saxophone (an alto and a tenor) in my personal collection.” - Steve Goodson, saxgourmet.com

Theobald Boehm invented a system of key mechanisms between 1831 and 1847 that revolutionized how flutes sounded and impacted the future design of all woodwind instruments—particularly saxophones and clarinets. In addition to larger holes, Boehm built his flute with "full venting," meaning all keys were open rather than covering some tone holes until a key opened them. He built a system of axle-mounted keys with a series of "open rings" fitted around other tone holes, such that the closure of one tone hole by a finger would also close a key placed over a second hole. This allowed him to locate the tone holes at acoustically optimal points on the instrument's body rather than where the player's fingers could easily cover them. The traditional fingering system for the saxophone closely resembles the Boehm system but with a few notable closed-hole exceptions (G#, Eb, C#). The Leblanc system more closely matches Boehm’s open key ideal.

The Leblanc Rationnel was designed in the 1930s according to Boehm’s principle: “Any note being emitted, all the notes below it should have their holes of emission open when the instrument is at rest.” While the System 100 and 120 horns of the 1960s refined this design and were more manageable to set up and repair, they are still challenging due to the number of articulated keys—every key and pad must be leveled and adjusted perfectly to close all those holes simultaneously—the keys have an arm attached to the rod from a lower tone hole cup depressing the cup of a higher tone hole. That cup, in turn, has an arm attached to it, which presses another, which then presses another. So, it’s a complex adjustment process…

The alto needed cleaning, oiling, and adjusting, so I took it apart. It was easier to get back together than I feared. These horns are well-built and have some mechanisms I had not seen before. I did not need to change any pads. They were custom and seemed to have snap-in resonators similar to Buescher's. There was a bag of spare pads in the case. Playing it once the horn was back together and in adjustment was a joy. The difference in venting and intonation was noticeable immediately. The keys are comfortable and quick, and the timbre throughout the range of the instrument is uniform. I enjoyed the tone of both the alto and the tenor. I understand why they have a cult following.

Some History of Leblanc (from their website):

Since its modest beginnings in America as a two-man shop, the company grew to a position of international prominence under the leadership of its cofounders, Leon Leblanc (1900-2000) and Vito Pascucci (1922-2003). The Kenosha-headquartered corporation employs a family of some 300 workers at three sites in Wisconsin (two in Kenosha, one in Elkhorn) and about 40 workers in La Couture-Boussey, France.

French roots

Leblanc in America traces its origins to the founding of Ets. D. Noblet of France in 1750, when the great flourishing of instrumental music at the court of Louis XV created a demand for musical instruments of all kinds. More than any other instrument manufacturer, Noblet refined and developed early woodwind manufacturing techniques, securing for the French nation its preeminent reputation for producing the best wind instruments in the world. Based in La Couture-Boussey for two and a half centuries, it is among the oldest continuously operating companies in France.

In 1904, having no heirs, the Noblet family passed its holdings to Georges Leblanc, descendant of a long line of distinguished French instrument makers. By the time he acquired Noblet, Georges Leblanc had gained a reputation as one of the finest woodwind makers in France. The workshop at the Leblanc headquarters in Paris became a meeting place of the great woodwind artists of the era. Working side by side with Georges was his wife, Clemence, who actually managed the factory while Georges fought during World War I.

From the beginning, the Leblancs were constantly guided by scientific principles and inspired by their inborn musical genius. As a result of this relentless dedication toward progress, Georges Leblanc and his son, Leon, set up their Paris workshop as the first full-time acoustical research laboratory for wind instruments. They recruited the talents of Charles Houvenaghel, regarded at the time as the greatest acoustician since Adolphe Sax.

The subsequent growth and success of G. Leblanc Cie. as a manufacturing entity was largely due to the work of Leon Leblanc, who in addition to his reputation as an instrument maker and businessman, was also a gifted clarinetist, holder of the first prize of the Paris Conservatoire, the first and only instrument maker to have held such an honor.

He had before him a brilliant career as a concert clarinetist, but chose instead to remain true to his heritage, feeling that he could make a greater contribution to music by combining the talents and sensitivities he developed as a musician with his skills as an instrument maker.

Together, Georges, Leon and Houvenaghel pushed the theoretical limits of instrument design to produce the first truly playable complete clarinet choir, ranging from sopranino to octo-contrabass, encompassing a range that surpasses that of the orchestral string sections. Perhaps even more significant, the Leblanc firm was the first instrument maker in history to manufacture clarinets with interchangeable keys, resulting in instruments that were easier to play in tune by artists as well as beginners.

As Leon Leblanc once noted, "Musicians of today should not be handicapped by the deficiencies of those before me. Acoustical, mechanical and musical improvements will be made. To this end, I have dedicated my life." Monsieur Leblanc served as chairman of the American company and president honoraire of the French firm until his death in 2000 at the age of 99.

The history of Leblanc in Kenosha, Wisconsin, dates to the last months of World War II and a chance meeting between Leon Leblanc and Vito Pascucci.

The American connection

Born in Kenosha, Vito Pascucci showed a marked interest in music and played cornet in the Kenosha High School band. He became fascinated with the construction and design of musical instruments and learned their repair as a summer apprentice at the Frank Holton Company (the Elkhorn, Wisconsin, brass-instrument manufacturer that Leblanc would later acquire), and then, while still in high school, augmented his family's income by operating an instrument-repair shop at his brother's music store.

In 1943, Pascucci was called into the armed forces. His instrument-repair skills were rewarded when he was assigned as a trumpeter and repairman to Army Field Bands, then to the Army Air Corps Band, led by Glenn Miller. He began with the Miller band in New Haven, Connecticut, then traveled with them to Europe. Stationed in England, Pascucci and Miller formed plans to set up a chain of music stores after the war.

Miller's untimely death put an end to those plans, but when the band was sent to newly liberated France, Vito paid a visit to G. Leblanc Cie., and his guide that day was Leon Leblanc. After service discharge in 1946, Pascucci returned to Kenosha, where Mr. Leblanc asked him to establish a foothold for the French company in America.