Two of my earliest and strongest musical memories are tied to Christmas: Odetta’s Christmas Spirituals album and going to see the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts production of Black Nativity written by Langston Hughes—they share many of the same songs. On Christmas Spirituals, Odetta plays guitar and sings, and Bill Lee (Spike’s father) accompanies her on bass. It was on repeat while my dad decorated our tree and sang along. When I was two or three years old, I saw Black Nativity for the first time—and then every Christmas for a handful of years. Their impact on me was immense and lasting. These songs introduced the Christmas story to me through a social justice lens and gospel sonority, laying a cultural and harmonic foundation that I still stand on.

In 2008, I recorded “What Month Was Jesus Born In?” and “Children, Go Where I Send Thee” on the Gumbo Family Holiday Album. Although I tried to avoid religious material, the songs lent themselves to funky interpretations and were cornerstones of my childhood Christmas memories.

Odetta Holmes (December 31, 1930 – December 2, 2008), known simply as Odetta, was an American singer, actress, guitarist, and civil rights activist. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1930, her family moved to Los Angeles when she was young. She studied opera and theater at Los Angeles City College before rising to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s as a folk singer known for her powerful voice, commanding stage presence, and passionate interpretations of traditional folk songs, spirituals, and blues.

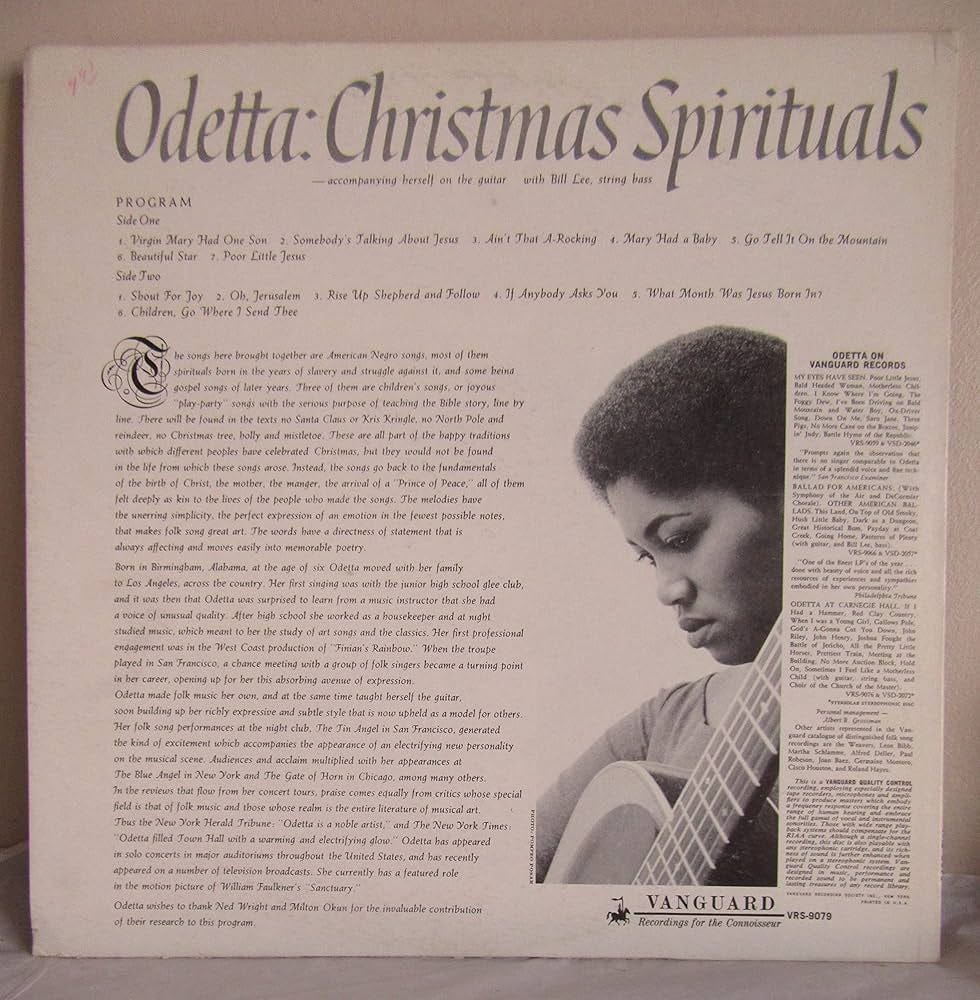

Odetta released Christmas Spirituals in 1960 on Vanguard Records, the same year my parents first heard her with Harry Belafonte at a concert in Boston. Spirituals, rooted in American slavery and oppression, carry themes of hope, freedom, and redemption, resonating deeply with the continuing struggle for equality. The album showcases the emotional depth of her powerful voice and the materials' cultural richness. Her distinctive performance style and arrangements bridged the gap between traditional spirituals and contemporary folk music. By recording spirituals, Odetta expanded folk music repertoire beyond traditional ballads and protest songs, demonstrating the genre's versatility and ability to encompass a variety of musical traditions. Her music transcended racial and cultural boundaries, attracting diverse audiences. It was layered with lyrics of strife and oppression, pushing white listeners to weigh the ongoing fight for civil rights. Odetta confronted racial and cultural divides by fostering understanding and empathy—profoundly impacting my perspective on American history, culture, and social conflict.

Beyond her activism, Odetta's musical influence was vast. Her recordings inspired countless musicians, including Bob Dylan, who cites her as a significant influence. She was recognized for her contributions to American music and culture with numerous awards and honors, including the National Medal of Arts. Her music remains a powerful testament to the struggle for equality and justice, and her unique voice still inspires me and many others.

Langston Hughes' Black Nativity premiered in December 1961. It retells the Nativity story from a uniquely African American perspective, incorporating gospel music, poetry, dance, and dramatic elements. Hughes, a prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance, drew inspiration from African American musical traditions, including spirituals and gospel music, to create a celebration of the Christmas story that resonates with marginalized communities.

At the time of its premiere (and for many years after), it provided a much-needed representation of African American culture and spirituality on the stage, challenging stereotypes and celebrating the unique contributions of black artists. Hughes' fusion of gospel music, poetry, and drama creates a vibrant and innovative theatrical experience that resonates with audiences. Its message of hope, faith, and community continues to inspire, making it a cherished holiday tradition for many. I saw it again at the Emerson Paramount Center in Boston last year for the first time since college and still loved it!

“On Dec. 11, 1961, at the 41st Street Theatre in New York City, six gospel singers made history. Backed up by only a piano and a B-3 Hammond organ, they performed Black Nativity by African-American poet and playwright Langston Hughes. He subtitled it “A Gospel Song Play” because it combined traditional gospel spirituals with narration about the birth of Jesus. After only 50 performances on Broadway, Black Nativity closed. But there was a legacy—a rare recording.

Conductor-pianist and music historian Aaron Robinson, having listened to the album for several years, set to the task of creating a score inspired by the legendary performance. Believing that music is both universal and inclusive, encompassing no barriers of race, creed or color, Robinson offered the opportunity to perform in this premiere concert version to all those who were interested in singing a style of music that was not normally a part of their tradition. The response was overwhelming, and Black Nativity – In Concert was born.”

I first saw it with my family when I was two or three. We went to the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts production in Roxbury and made it part of our holiday celebration for the next five or six years. My mother claims I fell asleep during the first year’s performance, but it became a well of inspiration that has never run dry. Now in its fifty-fourth season, the production has been an institution in Boston for generations.

Elma Lewis (September 15, 1921 – January 1, 2004) was prominent in arts education and community activism in Boston. In 1950, she founded a school of fine arts in Roxbury, MA, offering classes in various artistic, social, and cultural topics, including art, dance, drama, music, and costuming.

“The National Center of Afro-American Artists offers it production of Black Nativity to Boston—and all the world—as a gift to people of “good will” from all spiritual traditions and cultural backgrounds, through music, dance, spoken words and theater, Black Nativity lifts everyone toward a greater appreciation of our shared humanity. Its empathetic embrace of fragility and hope stirs us to commit anew to lives of peace and justice.”

Lewis's Black Nativity productions significantly impacted the cultural landscape in Boston and beyond. They provided artistic expression and community engagement opportunities while promoting social awareness and positive change. Lewis’s work helped solidify Black Nativity as a beloved holiday tradition, and her legacy inspires those seeking to use the arts for social change and community empowerment.

As I reflect on my childhood, I am grateful for experiences of spirit, celebration, music, and dance. Many showed me a world outside my own, which I quickly grew anxious to explore.